For a sport that requires a 54-man roster, it seems difficult to imagine a scenario where one or two players ensure a deep postseason run. Yet, for many NFL general managers, it feels like they believe that is the case. The NFL Draft is a great case study for examining how front office executives opt to build their teams. Overall, it seems like there are a few primary schools of thought. In one bucket, you have general managers who opt for a strategy of stocking the chest of draft picks; John Schneider of the Seattle Seahawks is a prime example of that model, as he’s traded down or out of the first round every year since 2011 to accumulate more draft picks. When Sashi Brown was the primary decision-maker for the Cleveland Browns, he built up a treasure load of picks, many of whom did not pan out.

Another school of thought seems to emerge from front offices who value the draft, but not to the extent of others. These are teams who will value the draft but probably not emphasize adding a surplus of picks; maybe they’ll scoop up an extra 1-2 through the compensatory system or a minor trade, but usually, they’ll be content to staying in their assigned draft position. This is, essentially, the “conservative” mindset, a style the Jacksonville Jaguars, Dallas Cowboys, and Arizona Cardinals traditionally take on. A third and final bucket to lump teams into are ones who value the draft solely because of the trade capital it brings. These are teams who love to utilize their draft picks to land a disgruntled superstar (Los Angeles Rams), aggressively trade up to land their ideal prospect (New Orleans Saints), or teams who consistently mortgage assets to bulk up their roster with NFL players (Pittsburgh Steelers). A lot of teams don’t clearly fit into these “buckets”, but generally speaking, there seems to be these three overall groups. The stockpiling of picks group, the “play it where it lands” group, and the “trade it” group. Today, we’ll be breaking down some of the common team-building strategies and begin to address what we believe is the most sound strategy to attacking, and subsequently winning, the NFL Draft.

Strategy #1: Does Stockpiling Picks Work?

A fascinating topic to me in general is tanking. It’s a team-building strategy that has become the new wave in professional sports, a strategy popularized by the Philadelphia 76ers’ process pioneered by Sam Hinkie. I’ve studied different tanking strategies for the past several years, specifically in the NBA, and my ultimate conclusion has become that I have not seen conclusive evidence that purposively fielding an inferior roster, losing games for better odds at a high draft pick, and trading valuable assets for draft capital is a successful strategy. Then again, due to the recency of the measure, the jury could still be out. Yet, while tanking has been limited primarily to the NBA for some time, it is slowly trickling its way into other sports, particularly MLB and NFL. The Miami Dolphins started their hoarding measures this past year, shipping out Laremy Tunsil, Kenny Stills, Minkah Fitzpatrick, Jarvis Landry, and others for a stockpile of picks. Now, Miami has three first-round picks in this year’s draft, a coaching staff that vastly overachieved last year, and a plethora of free agent additions like Byron Jones, Shaq Lawson, Jordan Howard, Ereck Flowers, Kyle Van Noy, and others. Will this stockpiling strategy work for the Dolphins? The biggest contrast between the Dolphins and tanking teams in other leagues is that Miami didn’t intentionally lose games. The Dolphins went out every week playing their best roster to win and ultimately, it led to overachievement, the foundation of a strong culture, and enough interest from free agents to want to join. In a sense, Miami’s competitive nature could accelerate their rebuild, even if it cost them the shot at a top-3 pick, a prize that usually feels like a championship trophy to a tanking team.

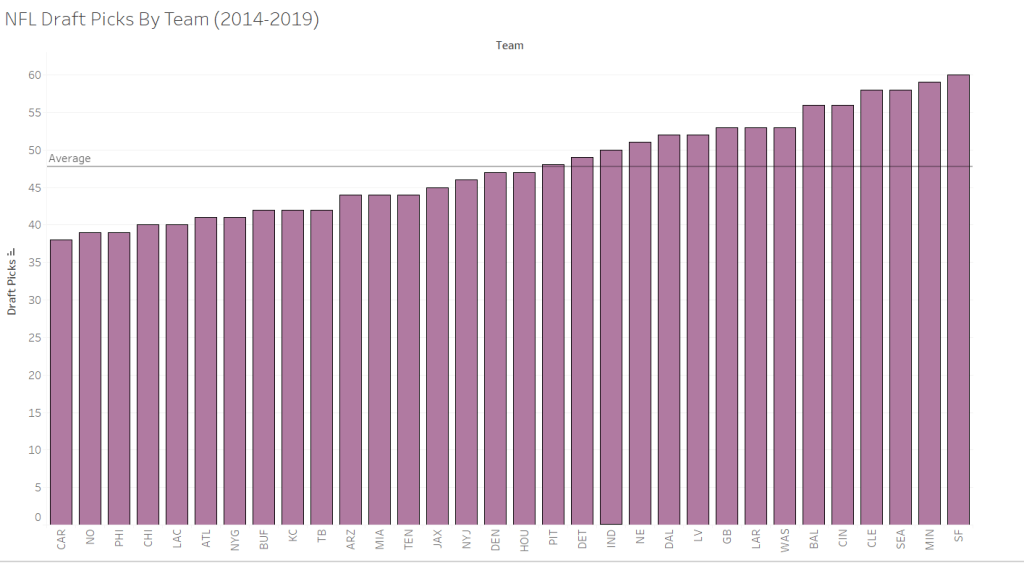

Regarding this first “bucket” of teams in the NFL, a fascinating examination of data surrounding draft picks brings about some interesting conclusions. While there are seven rounds in the NFL Draft, there is a total of 255 picks because of additional compensatory selections awarded through free agency transactions. If every NFL team were awarded an equal number of picks, that would equal 7.97 draft picks per team this year. Obviously, however, that is not the case. There are plenty of teams that opt to stockpile picks, whether it’s from accumulating extra selections by trading down or taking advantage of the compensatory system by letting free agents walk (Baltimore and New England both do this better than anyone). Over the past six NFL Drafts, here’s a look at the amount of picks each team has held:

Over the past six NFL Drafts, the San Francisco 49ers, Minnesota Vikings, and Seattle Seahawks (tied with the Cleveland Browns) were the leaders among draft picks. However, our ideal strategy in examining this method is to determine if a correlation exists between the amount of draft picks a team has and their winning percentage. If the theory that stockpiling picks is successful, then ideally there’d be fairly strong positive correlation between number of picks and winning percentage. Take a look at the data here:

As you can see present in the graph, there is no correlation between number of draft picks and winning percentage. In fact, the actual correlation coefficient is 0.03, which illustrates that there is literally zero relationship.

With that analysis being conducted, does that mean that having more draft picks is a futile strategy? Well, not necessarily. Among the 17 teams who had an above average winning percentage over the past six seasons, over half also had an above average number of draft picks while two more were within .9 picks of reaching the average as well. Additionally, teams that reached the playoffs last season had an average of 8.19 draft picks per year, while non-playoff teams had an average of 7.83 draft picks per year. While that is not a significant difference, there does seem to be some merit for having a lot of draft picks.

While there is no evidence that having more picks leads to more wins, an interesting finding that certainly is worth sharing regards trends in the NFL. The top four teams on the quickest rise (based on increased wins from 2018 to 2019) were the San Francisco 49ers, Green Bay Packers, Baltimore Ravens, and Buffalo Bills. The four teams on the steepest decline (based on decreased wins/future outlook) are the Los Angeles Rams, Chicago Bears, Los Angeles Chargers, and Houston Texans. Take a look at their draft pick comparisons over the past three and six years:

| Draft Picks by Group | Average Last Three Drafts | Average Last Six Drafts |

|---|---|---|

| Rising Teams (SF, GB, BAL, BUF) | 8.75 draft picks | 9.08 draft picks |

| Declining Teams (LAR, CHI, LAC, HOU) | 7.33 draft picks | 7.79 draft picks |

This discrepancy in draft pick totals almost confirms a notion that’s long been held: building through the draft leads to success. The San Francisco 49ers are a team that has invested heavily in the draft during the post-Jim Harbaugh era, accumulating 60 draft picks over the past six seasons. The result is a formidable defense, talented offensive line, and an entire team that is elevated because of Kyle Shanahan. Baltimore is another team that consistently emphasizes having a plethora of picks and utilizing the compensatory system to their advantage. The result led Baltimore to having enough ammo to trade up for Lamar Jackson in the 2018 NFL Draft and to the Ravens becoming a Super Bowl favorite. Overall, the four teams on the steepest ascension have been among the clubs most heavily investing in cheap, young, controllable players. Considering the data listed above which shows that teams including Seattle, Minnesota, and New England, yearly playoff fixtures, have been prioritizing their draft assets, there is certainly an argument to be made that more draft picks might lead to greater on-field success.

As for the flip side, let’s examine the teams in decline. The Rams, Bears, and Chargers all took a significant step back last season primarily due to three factors: poor offensive line play, an average/below average quarterback forced to make the majority of offensive plays, and some bad injury luck (LA with Gurley and Cooks, CHI with Hicks and Smith, LAC with James, o-line). However, among the four teams in decline, three have something oddly in common: they all traded up for a quarterback within the past five seasons (LA, CHI, HOU). As for the teams in ascension, Buffalo and San Francisco both traded down with teams looking for a quarterback. Now, it’s important to note that Baltimore also traded up for a quarterback (Lamar Jackson), but Baltimore did not give up the draft capital the other teams did. The Rams gave up two firsts, two seconds, and a third (while getting a first, fourth, and sixth), Chicago gave up a first, third, fifth, and second (while getting a first), while Houston gave up two firsts (while getting a first and subsequently already trading other picks, including a second to dump Brock Osweiler). Baltimore, on the other hand, gave up two seconds and a fourth (for a first and fourth). The disparities between both parties are evident: the declining teams valued the draft for trading up, the ascending teams valued the draft for the picks themselves.

Is Prioritizing a Quarterback Smart?

When we frequently mention NFL Draft busts, the most notable ones who come to mind are quarterbacks. The NFL as a whole emphasizes the quarterback position to the extreme, so much so that I think there’s this false notion that having an elite quarterback is essential to winning a Super Bowl. We’ve extensively discussed quarterback play through our articles, (including the Kirk Cousins Line you can read here) and while having an elite quarterback makes things so much easier, having the quarterback alone doesn’t even guarantee a playoff berth. After all, Drew Brees and Aaron Rodgers have missed the postseason multiple times throughout their careers. It is why prioritizing a 30-40 man deep roster is so important when building a team, because if you have a roster that complete, you have an advantage over every other team.

Now, with that being said, there’s an important point to emphasize: having an elite quarterback does make things easier. However, does the data suggest trading up for a quarterback, or taking one at a high pick because of the importance of position, is a smart move? Well, let’s take a look here at the average draft positions of current NFL starting quarterbacks (assuming Joe Burrow goes #1, Mitchell Trubisky starts):

| Quarterback Draft | ADP Among Starters | ADP (Drafted 2000-2015) | ADP (Drafted 2015-2020) |

| ADP Starting QBs | 50 | 67.93 | 34.18 |

This data illustrates a pretty interesting point: the average draft position among all starting quarterbacks is the 50th overall pick, yet quarterbacks are consistently taken in the top-10. Now, the key thing to illustrate is the 50th ADP is vastly skewed because of recent quarterbacks drafted in the top-10 who are still starting. As of quarterbacks experiencing the best longevity, the ADP was in the early third round. Yet, so many teams not only take a quarterback in the first round, but they subsequently trade up for a quarterback.

Let’s explore this idea further and really flesh it out. The biggest blunder of trading up was the Chicago Bears moving up to the #2 overall pick to select Mitchell Trubisky. So far in his NFL career, Trubisky has been a below-average starter and he really bottomed out last season, so much so that the Chicago Bears mind-bogglingly traded for Nick Foles and his $20M AAV contract. In return for San Francisco giving up the 2nd pick, they moved back one spot in the Draft and accumulated three extra draft picks. Another team who traded down to accumulate a monster haul of assets was the Tennessee Titans, who moved down fourteen spots to allow the Los Angeles Rams to get the #1 overall pick. Tennessee also gave up a fourth and sixth round pick, but they were able to acquire two extra second-round picks, a third round pick, and an extra first-round pick. The Rams obviously took Jared Goff, a selection that was solid, but probably not worthy of the top draft selection, especially when Carson Wentz was drafted next. However, the excess draft selections for Tennessee allowed them to find numerous key contributors and subsequently cash in on the extra assets. Tennessee added Derrick Henry, Jonnu Smith, and Corey Davis with three of the picks and all were impact players throughout their improbable run to the AFC Championship Game.

In order to be fair, while there are stories of failure when trading up for a quarterback, there’s also stories of success, namely Patrick Mahomes, Deshaun Watson, and Lamar Jackson. Yet, what put all of those teams in the position to make those deals was the emphasis each club had put on the Draft in prior years. Essentially, these teams capitalized on the hoarding of their own picks in order to land the guy they were convinced was a star. The Kansas City Chiefs drafted Patrick Mahomes in 2017, and in the three prior years, they had a total of 24 draft selections, which is above average. The Houston Texans selected Deshaun Watson in 2017 and in the three prior years, had a total of 24 draft selections. The Baltimore Ravens drafted Lamar Jackson in 2018 and in the three prior years, had a total of 27 draft selections. The high valuation that all of those clubs put into the Draft enabled them to come away with their superstar. Even the Rams, whose trade-up and subsequent selection of Goff has been a success (even if Goff hasn’t been top pick quality), was largely forged because of their investment in draft selections, drafting 19 players in the two years prior to the trade.

As a quick aside, it might seem counterintuitive that I pointed out Houston’s lack of draft picks in the section before but now commend their stashing of picks to trade for Deshaun Watson. To clear things up, the move for Watson in of itself was smart and largely possible because they prioritized drafting players. However, after the selection of Watson, instead of continuously reinvesting in draft picks, they viewed them as “assets” and began shipping them off in trades. The post-Watson decisions to relatively deemphasize the Draft has ultimately led to their declining nature.

A Collection of Other Draft Strategies

What’s the Better Strategy: Best Available Overall or Best Available at Biggest Need?

This is a classic question that is often brought up around the NFL Draft. Some general managers opt for the best player available overall each year and on occasion, it works out. Most teams, however, choose to fill needs, which sometimes works as well. Overall, there isn’t conclusive evidence to determine if one strategy is better than another for a variety of reasons. First, team needs, even if some are obvious, are primarily subjective. While many of us may currently argue that the New England Patriots need a quarterback, the organization may feel confident with Jarrett Stidham being their next guy. Therefore, the Patriots selecting a defensive end, for example, in Round 1 could appear to us as selecting the best player available overall, while their front office might view it as selecting the best available player at what they deem is their biggest weakness.

However, an interesting thought I want to throw out for debate is this: is filling a need more important than trusting the actual talent evaluation? For example, let’s say the Denver Broncos deem their biggest need to be a cornerback, and at the 15th pick, the best cornerback remaining is Kristian Fulton, who is ranked 35th overall on their board. Should Denver opt for Fulton, who they have graded as an early second-round talent, or select Tristan Wirfs, who they have ranked 12th on their board but doesn’t fill a pressing need? It’s not the best example, but it’s an interesting thought exercise. Personally, I believe this is a situational issue and if there’s such a stark contrast in player rankings, then you should probably opt for the best available player.

Is Drafting a Running Back in the First Round Really that Bad?

The running back position is arguably the most underappreciated in the NFL. Many pundits, front office executives, analysts, etc. believe that running backs are extremely replaceable for a few reasons: one, they don’t have great longevity (the dreaded 30-year old mark), two, a lot of their success is dependent on the offensive line play, and three, there’s so many talented guys that prioritizing one is a luxury, and luxury picks don’t win games. To be honest, when looking at past Super Bowl champions, not one has prioritized the running back position nor has had an elite running game. According to Football Outsiders, here’s a look at the Super Bowl Champion’s rushing efficiency for the past five years:

| Super Bowl Champion | Rushing Efficiency Rank | Passing Efficiency Rank |

| 2019-20: Kansas City Chiefs | 14th | 2nd |

| 2018-19: New England Patriots | 9th | 4th |

| 2017-18: Philadelphia Eagles | 15th | 6th |

| 2016-17: New England Patriots | 15th | 2nd |

| 2015-16: Denver Broncos | 20th | 25th |

A clear conclusion has emerged: Super Bowl winners are traditionally, much more efficient and better at throwing the football than running it. This easily begs the question of why prioritize drafting a running back in the first round when Super Bowl champions traditionally have average rushing attacks and elite passing attacks?

Well, to answer why passing offenses win Super Bowls, the easiest way to illustrate it is with numbers:

| Passing vs. Running | Average Completion % | Average Yards Per Completion | Expected Yards Per Pass | Expected Yards Per Rush (Average Yards Per Carry) |

| 2019-20 | 63.5% | 11.4 | 7.24 | 4.3 |

| 2018-19 | 64.9% | 11.4 | 7.40 | 4.4 |

Clearly, passing is the most efficient and effective form of offense. That doesn’t mean the running game isn’t important, but having a prolific passing attack is far more important. This statistic is probably a strong indicator of why teams value an elite quarterback so much and sometimes falsely believe that they need to draft one in the first round, specifically in the top-10 picks.

However, when pivoting to drafting the running backs high, there does seem to be some merit to prioritizing a talented running back. Among the top ten running backs last season in rushing yards per game, their average draft position was 55.5, which is fairly close to the current average draft position of starting quarterbacks, which was 50. Among the top ten running backs last season in rushing yards per attempt (and started at least eight games), the average draft position was 53.8, once again similar to the ADP of starting quarterbacks.

Now, let’s dispel one notion quickly: by no means am I arguing that running backs are as valuable as quarterbacks. However, I think this trepidation towards investing a high draft pick in a running back is, frankly, a bit misinformed. Looking back at the past five NFL Drafts, running backs who went in the first round include Christian McCaffrey, Saquon Barkley, Todd Gurley, Ezekiel Elliott, Melvin Gordon, and Josh Jacobs. To be frank, the only running back who was a first-round pick that has been a non-factor is Rashaad Penny, and Penny has shown great promise when he’s been healthy.

To answer the strategy decision, I absolutely believe a running back is worthy of a first-round pick, but only if they’re a significant threat in the passing game. Considering how much more efficient and effective throwing the football is, investing heavily in an asset who encourages inefficient offense seems counterproductive. Unless the player is a complete athletic freak (Derrick Henry), odds are the running back isn’t worth a first-round pick if they don’t contribute in the passing game. Talent is talent and it’s silly to draft a wide receiver you believe to be an interior offensive talent over a superior running back simply because of the stigma surrounding the position. However, landing a running back who contributes in the passing game is certainly a player worthy of a first-round selection. After all, you could argue the five best all-around running backs are Christian McCaffrey, Saquon Barkley, Alvin Kamara, Ezekiel Elliott, and Derrick Henry. The average draft position of those players? 25.2.

What is the Seattle Seahawks’ Draft Formula?

John Schneider, the General Manager of the Seattle Seahawks, is the header photo for this article, in large part due to his track record of success in the NFL Draft. Schneider took over as GM in 2010 in conjunction with Pete Carroll and since then, the Seahawks have done nothing but win. The Seahawks first two seasons in the Carroll/Schneider era saw them go 7-9 each year, but they began to improve in Year 3, aka the season when Russell Wilson became the starter. Overall, since Carroll and Schneider took over, the Seahawks have a regular season record of 100-59-1 and that stretch has included a Super Bowl victory, a near Super Bowl victory (Malcolm Butler), and a total of eight Playoff berths, including that first 7-9 season.

One reason why the Seahawks have been able to sustain this success over the past decade has been because of John Schneider’s drafting acumen, but a large part of his success has been his ability to stockpile picks. As mentioned in the data above, the Seahawks were tied for the 3rd most draft selections in the past six years and during Schneider’s time, he’s drafted players like Russell Wilson, Earl Thomas, Bobby Wagner, Richard Sherman, Kam Chancellor, Doug Baldwin, Frank Clark, and K.J. Wright. The craziest part of Schneider’s success is that of all the picks listed above, only Earl Thomas was a first-round selection. Schneider has been a genius at not only evaluating talent, but properly building up a treasure chest of picks in order to be advantageous during the draft festivities.

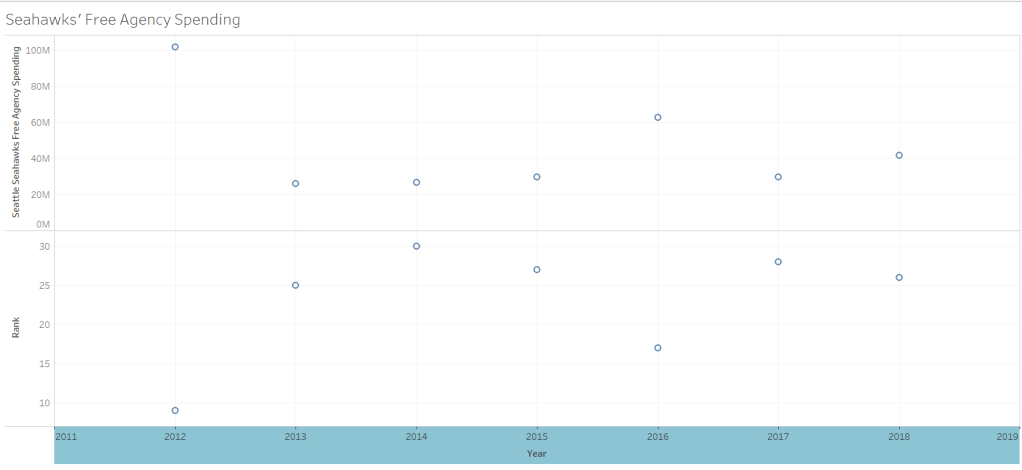

While the Seahawks have been able to sustain such success over the past decade, an incredible fact to point out is that Seattle rarely dips their toe into free agency signings. From 2012-18, here’s a look at where Seattle has ranked among NFL teams in free agency spending:

From the graph above, you can see that outside of one year (2012), the Seahawks ranked below average in terms of free agency spending and in five of the seven seasons listed, they ranked in the bottom-eight. Simply put, the Seahawks have never been a team to splurge in free agency, yet they’ve been a dominant team in the past decade. From 2010-2019, the Seahawks were tied with New Orleans for the 4th-highest win percentage in the NFL, and behind only New England, Pittsburgh, and Green Bay. In that same span, the Seahawks had a total of 97 draft picks for an average of 9.7 picks per year, way above league average.

Now, John Schneider has a method to drafting, with his biggest strategy including trading down or out of the first round. Since 2011, Schneider has done just that every single year, and as mentioned previously, he’s had a ridiculous amount of success on Day 2 and Day 3, finding gems like Wagner, Wilson, Sherman, Chancellor, Wright, Byron Maxwell, Super Bowl MVP Malcolm Smith, Chris Carson, Doug Baldwin, Tyler Lockett, Golden Tate, among others. Yet, isn’t it a bit odd that the Seahawks have only drafted in Round 1 six times since Schneider took over? (Note: They’ve had seven total picks but in 6/10 drafts Schneider has been a part of the Seahawks have had a first-round selection).

From an economist’s point of view, Schneider is an absolute genius when it comes to the NFL Draft. Last season, the 25th overall pick (Marquise Brown) agreed to a 4 year, $11.787M deal, leading to an AAV of $2.95M (roughly). However, the 36th overall pick (Deebo Samuel) agreed to a 4 year, $7.247M deal, leading to an AAV of $1.81M (roughly). Now, those are relatively small figures considering the salary cap was set at $198.2M for this season, but the economic trade-off is interesting. When creating a draft board, it’s tough to quantify how far apart players are. For example, how can you quantify the difference in talent between your 25th ranked prospect and 35th ranked prospect? Considering NFL teams likely rank north of 400+ prospects, I’d be willing to bet that the difference regarding players ranked within 10 spots of each other is quite slim. With that being said, isn’t it economically sound to trade out of the late first-round into the second, to not only acquire extra draft capital, but also to save a bit of money and land a player who is likely comparable to who you could’ve selected in Round 1? It’s a unique detail that John Schneider gets to a T.

So, not only is John Schneider able to add extra draft picks by either trading down or out of Round 1, but he’s also able to save a decent amount of money while selecting what is likely a comparable, or better, player on their draft board. This economic trade-off, or “opportunity cost”, is an essential concept for NFL front office executives and Schneider has it mastered. Schneider has shown his hand for years and it consistently works, yet no team is quick to copy-and-paste that model into their own draft strategy. Schneider believes the trade-off between trading back/out of the first round, accumulating extra draft picks, and getting a cheaper, but comparable player is the advantageous move over staying put and picking. What has that strategy led to? A winning percentage of 62.50% over the last decade, two conference championships, a Super Bowl, and plenty of gems found on Day 2 and Day 3 of the NFL Draft. If I was running an NFL franchise, a prime person for me to learn from would be John Schneider.

Last Thought: The Virtual Impact

While our “consulting/advisory” section is largely over (and we hope you enjoyed!), I wanted to end with my thoughts on the virtual component on the NFL Draft and what ramifications we can see. To start, the Pittsburgh Steelers General Manager, Kevin Colbert, suggested that each NFL team gets three extra draft picks in the 2020 NFL Draft because of the Coronavirus outbreak (link to the full article is here). That suggestion by Colbert caught my attention for a few reasons. One, the Coronavirus pandemic has certainly created challenges to the traditional pre-draft process, and most executives (like Colbert) are probably more hesitant than usual in selecting players without having Pro Days, in-house visits, or individual workouts. Two, it’s that having a lot of draft picks is pretty valuable, as Colbert acknowledges that the additional uncertainty of the prospects should lead to the NFL essentially giving each team a greater “buffer”.

Jordan Reid from The Draft Network (one of the best NFL sites out there, for the record) wrote a great article two weeks ago that included a quote from a scout that said, “You’re going to see a record amount of trades on Day 2 and Day 3 for future picks,”. (Link to the article is here–would highly recommend giving it a read). To me, this is a fascinating development and kind of goes hand-in-hand with Colbert’s comments: there is greater uncertainty than normal this year and because of that, general managers are unlikely to take on riskier moves.

This belief highlights a few big things for me to point out: first, it’s that many general managers are risk-adverse especially when it comes to job security. The NFL Draft is where GM’s are judged the most, so it does seem logical that general managers would rather not hedge on more uncertainty than normal. However, if this scout is correct, I think it will be easy to tell which teams are the smartest: they’ll be the ones trading for picks in this year’s Draft. I have a few reasons for my belief. First, there’s a basic economic principle on display here: supply and demand. If teams desire to push their draft capital towards a future year where greater certainty surrounding prospect valuation can be had, then it will lead to a surplus of available picks on the trading block, ultimately lowering the asking price and subsequently, the capital needed to swing a trade. In a sense, even if greater uncertainty is present than normal, does the risk factor outweigh the value you’re getting? I’m assuming teams have certain algorithms or valuation charts to help them with draft pick trades, but if, for example, ten teams wanted to move out of the fourth round for a future draft pick, that would naturally lower the asking price due to excess supply and, presumably, low demand. In that regard, you have to think the adjusted risk factor in the algorithm would probably be outweighed by the perceived value.

Getting away from economic talk and theory, another point I want to mention is my own thought. For the record, by no means am I a professional (or even amateur) NFL scout, but I have a hard time believing that a player’s Pro Day and/or in-person visit would drastically shift a team’s ranking of the player (and by drastic, I’m talking a 30-40+ ranking shift). This is when NFL front offices should be reviewing their past data and decisions to determine how big of an effect those Pro Days and in-person visits have had in crafting the board, and if those events have been a positive or negative in the overall evaluation process. If my belief that Pro Days and in-person visits don’t drastically shift a team’s ranking of the player, then you can ask the question of, “Does the virtual setting of the NFL Draft really carry much more risk than normal?”. If Pro Days and in-person visits don’t drastically alter the board, then the answer to that question is probably no.

Now, let’s tie these two points together. If there is a surplus of picks available, it will lower the asking price and subsequent package to obtain one. In that sense, economically-sound teams (Seattle) will likely take advantage of the cheaper-than-usual cost of acquiring a pick. However, a team’s desire to acquire more picks for this year’s draft is reliant on the risk factor. The additional risk with this year’s NFL Draft comes from a lack of Pro Days and in-person visits. If you’re a team whose data indicates that those events don’t drastically alter the board, then there really isn’t that much more risk this year than normal, which should encourage these franchises to take advantage of the low cost of acquiring picks. My hypothesis is that there really isn’t that much more risk in drafting players this year compared to other years, and if that reigns true, then a lot of teams who acquire extra picks for a cheaper cost will look very smart in the future.

As a final point, I just want to clear up this “risk assessment” issue. Like I mentioned, by no means am I a front office executive or scout, so I really don’t know the weight these individuals place on Pro Days and in-person visits. My gut and instincts has led me to believe that they can’t drastically alter a player’s ranking, especially after you watched game footage for 2+ years of the athlete and presumably talked to them digitally (and possibly with the coaches as well). However, one area that I do think brings greater risk is with players’ medicals. Not having in-person workouts for certain players will drastically increase the risk associated with drafting said player. I think that is why current reports are indicating that Tua Tagovailoa is falling in the NFL Draft and has been removed from certain teams’ boards.

Final Thoughts

Overall, the data surrounding the NFL Draft presents a murky picture, and similar to the quarterback decision-making process, it’s tough to implement a black-and-white, universal rule for a situation that is so multifaceted and complicated. I don’t believe one strategy exists that is “better” than every other one, but one thing I am fairly certain of is that understanding trade-offs and economic principles provides teams with an edge on draft night. While no correlation is present among number of draft picks and winning percentage, certain trends exist that illustrate teams who experience success on the field typically value selecting players at the NFL Draft to a higher degree. As evident by teams on a steep upward trend, building through the draft remains one of the best team-building strategies around, but the trick is to continuously invest in that process, and not forgo it the minute deep playoff runs appear. While running backs might be slapped with an unfair stigma while quarterbacks are perched on glory pedestals, the data indicates that top-tier running backs are, on average, first-round picks while starting quarterbacks, on average, are second-round picks. This by no means makes running backs more valuable than quarterbacks, but it does show that “selecting a running back in the first round” isn’t a sin.

At the end of the day, while the NFL Draft is a grand spectacle that is the culmination of individuals’ years of hard-work, the process itself is a complicated web of data, evaluation, and human error. There’s no perfect-decision making model for teams to deploy to steer clear of the next Jamarcus Russell or Justin Blackmon, there’s no pristine algorithm to steer a franchise to the next sixth-round wonder. Rather, the principles guiding the best NFL teams include economic theory, data analysis, and the valuation of draft picks. Finding the right way to combine all of those tools and convert them into a draft strategy is how teams win and why teams win. What makes the NFL Draft such a fun event is the promise of a new future for many teams. Yet, that promise likely hinges on a myriad of strategies aiming to solve a system that has no answer.